reform entices

economic elites

and clouds the

future of

the elderly

Available in

PDF format

Jan Hagberg & Ellis Wohlner

RETIREMENT

An adequate national

pension system based

on principles of social

justice would include

the following elements:

| • | Genuine social security, ensuring a decent standard of living for all pensioners |

| • | Universality, i.e. including the entire population |

| • | Guaranteed minimum benefit |

| • | Financial stability |

| • | Moderate relationship to pre-retirement earnings |

| • | Perceived by the general public as fair |

| • | Easy to understand |

| • | Predictable benefits |

| • | Low administration costs |

| • | Low vulnerability to market fluctuations. |

"decent… relationship…

viable… fair… easy", etc.*

are relative, and can only

be understood in relation

to other alternatives.

The pension reform that went into effect in 2001 has been presented as a necessary response to the ”welfare paradox” that confronts virtually all developed countries. The paradox is that a steadily shrinking work force, working fewer hours, must support a steadily expanding population of retirees.

This is a trend that has caused widespread and frequently exaggerated alarm over the solvency of national pension schemes. The Social Security system of the United States, for example, has in recent years come under intensifying attack from those who claim, mainly on the basis of dubious assumptions, that it is on the verge of bankruptcy.

The Swedish pension reform has therefore attracted considerable attention abroad, since it is said to provide a solution to the threat of fiscal insolvency posed by the welfare paradox and other factors. Ironically, the enthusiasm appears to be greatest among interests which in the past have often heaped scorn on Sweden for its general-welfare system. These include the enemies of Social Security in the United States, and the international business press (see, for example, "Pensions: Time to Grow Up”, in The Economist, 16-22 February 2002). Approval by such interests should signal a warning to those who are devoted to the traditional Swedish model of general welfare and social solidarity.

It turns out that there are, indeed, several reasons to be concerned about the likely effects of the recent reform on the well-being of Sweden’s senior citizens. Among other things, the new system will almost certainly result in reduced pensions for a large majority of citizens, and promote social injustice by yielding varying retirement incomes for individuals in similar circumstances. It also implies an enormous transfer of economic power from society as a whole to special interests, and stimulates the flow of capital out of the country.

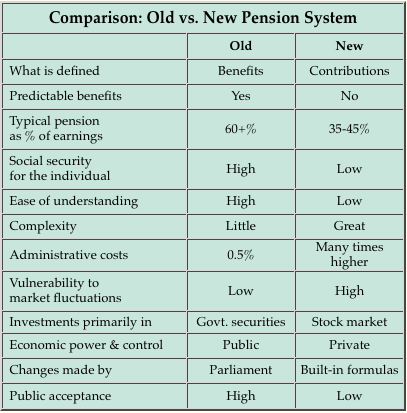

The problems and deficiencies of the new pension system become evident when compared with its abandoned predecessor.

*Standard

Income Unit (SIU)

is a Swedish accounting

device which is used in

the calculation of social

benefits, income levels,

tax tables, etc. The value

of an SIU in 2002 is set

at SEK 37,900 (roughly

US$3,800 at the end of

May 2002). Roughly 85

percent of the Swedish

labour force has incomes

less than 7.5 SIUs.

The old pension system, which went into effect in 1960, consisted of two components: a universal basic pension (”FP”) to anyone who had resided in Sweden for a total of at least three years; and a supplementary pension (”ATP”) based on the number of years worked and the amount of earned income. Both components were keyed to the Standard Income Unit (SIU)*, and were automatically adjusted for changes in the Consumer Price Index.

With this two-part system, those who retired at age 65 with at least thirty years of eligible work experience received pensions averaging 60-65 percent of pre-retirement earnings. (Most people will also have had a collectively negotiated supplement.) This was among the highest pension levels in the world, and greatly improved the standard of living among the Swedish elderly.

The old system had a number of clear advantages. It was easy for most citizens to understand, future pension benefits were predictable and the purchasing power of the elderly was maintained. It was also fairly simple and inexpensive to operate: The cost of administration was only about 0.5 percent of total benefits.

Due to these factors and the relatively comfortable pensions it provided, the old system enjoyed wide acceptance among the general public. But due to such factors as the welfare paradox noted above, concern began to mount during the 1980s that benefits would eventually outstrip revenues. Critics pointed to a number of perceived shortcomings, including the following:

• The system was ”unfunded”, but it is very doubtful whether a national pension system can be ”funded”; see below.

• Benefits were not linked to real economic growth or demographic changes.

• The system was financially ”unstable” (whatever that means)

• The relationship between the individual’s contributions and benefits was not strong enough.

• Political support for the system was unstable, it having been approved in parliament by a margin of only one vote.

*Note: Although it is often made, the distinction between ”funded” and ”unfunded” programmes is not all that clear. See "Funded“ vs. “Unfunded“.

The primary goal of the pension reform is to achieve automatic, long-term financial stability. The self-evident social goal of a pension system-- to maintain the living standards of the elderly-- is no longer self-evident.

Future pensioners are confronted with a choice of nearly 700 funds offered by some seventy financial institutions including banks, insurance companies and mutual-fund operators.

Of course, there were conflicting views about the urgency and the relative importance of these deficiencies. But there was general agreement that something would have to be done in order to prevent the system from collapsing.

The obvious solution was to make adjustments to the existing system, and pension experts recommended three, in particular:

• indexing benefits to real economic growth instead of consumer prices

• raising the normal retirement age

• providing for a reduction in benefit levels in response to demographic changes, if and when it actually became necessary.

Modifications of this sort were entirely feasible. But that option was ignored in favour of the very different thing which is now being cited by fiscal conservatives as the very model of a modern pension system.

The primary goal of the pension reform is to achieve automatic, long-term financial stability. The self-evident social goal of a pension system-- to maintain the living standards of the elderly-- is no longer self-evident. That is a secondary concern of the new system, which will almost certainly result in reduced living standards for the majority of pensioners. Certain subgroups, such as young people who are late in entering the labour market and middle-aged women, are likely to be especially disappointed when they reach retirement age.

The new system is based on lifetime earnings and is financed by a levy of 18.5 percent on wages. Sixteen percent is allocated to a ”pay-as-you-go pension” and 2.5 percent is placed in a ”premium reserve pension” which must be invested in mutual funds.

According to its authors, the reform has resulted in a stable system which automatically adjusts to changing demographic trends. They also claim that the system is linked to national economic performance, particularly with regard to the 2.5 percent of earned income that is required to be invested in mutual funds. Future pensioners are confronted with a choice of nearly 700 funds offered by some seventy financial institutions including banks, insurance companies and mutual-fund operators. Up to five funds may be selected at any given time, and cost-free transfers are permitted on a daily basis. The pension credits of those who do not make any active choice are placed in a state-operated fund established specifically for that purpose.

Defenders of the system have offered reassurance that the stock market will rise again and, with it, the value of market-related funds. What they have not done is to offer any solace to those who have exercised the poor judgement to reach retirement age at a time when the value of their pension funds has declined.

Exactly what all this means for the pensions of the future is a mystery to which no one appears to have a satisfactory answer. But it is already apparent that the new system is burdened with a number of serious problems.

For one thing, it is vastly more complex and difficult to understand than its predecessor. It is also much more costly to administer: A special national agency had to be established just to handle the traffic in mutual funds. One indication of the system’s complexity is that its introduction was delayed by several years due to difficulties in developing an adequate computer system. Whether that problem has been solved remains to be seen, but large sums of tax money have already been expended for that purpose.

One thing that no computer system will ever be able to do is to predict future retirement benefits. Although the amounts of contributions are clearly defined, the benefits to be paid are not. This is due especially to fluctuations in the value of the mutual funds in which citizens are required to invest. Those who choose more wisely or more luckily will receive higher pensions than those whose choices are not so fortunate-- even if their circumstances are identical.

Thus far, the vast majority of those involved have been losers. Since the funds are tied to the stock market, the recent crash has resulted in widespread losses, some much greater than others. Once again, people are learning the hard way that the stock market can go down as well as up.

Defenders of the system have offered reassurance that the stock market will rise again and, with it, the value of market-related funds. What they have not done is to offer any solace to those who have exercised the poor judgement to reach retirement age at a time when the value of their pension funds has declined. They will have to live with the financial consequences of that unfortunate timing for the rest of their lives.

Even if a positive result could be guaranteed (as noted, an impossibility) the question remains as to how many Swedes really want to devote time and effort to figuring out which of nearly 700 mutual funds to invest in. The largest single category (86% in 2002) consists of those who choose not to make any choice; their credits are invested by default in the state-operated fund, which has been one of the less dreadful performers to date.

The logic of the new pension system ignores the most fundamental rule: Never invest more than you can afford to lose. For the vast majority of future pensioners, that amount is nil.

In general, the system is based on faith in the stock market‘s ability to generate higher investment returns than the economy as a whole. It is a faith that appears to be highly exaggerated, as indicated by the following summary of the relevant trends during the 20th century:

“Between 1920-1929, the value of stocks in the United States increased by over 400 percent. Then came the great crash of 1929, followed by a modest recovery until 1936. But from that year until 1949, stock values declined. True, the level in 1949 was twice that of 1920; but that doubling of value happened to be exactly the same amount as the U.S. Gross Domestic Product (GDP) increased during the same period.

“The stock market climbed again during the period from 1950-1960. Then followed fifteen years of slow decline. In 1979, the value of the stock market was twice that of 1950-- which was, again, the same amount that GDP had increased during the same period.

“From 1980 onward, the stock market climbed straight toward heaven for what seemed likely to be all eternity. A sobering decline has since occurred and, if history repeats itself, it is more probable that the stock market will fail to return to its previous heights than that it will experience a new long-term upswing.” (Translated from Swedish text of Sten Ljunggren, “Veckans diagram 10” in Etc. magazine.)

The logic of the new pension system also ignores the most fundamental rule for playing the stock market: Never invest more than you can afford to lose. For the vast majority of future pensioners, that amount is nil. It should also be noted that not even the ”guaranteed portion” of the new pension is guaranteed. It may decline in value, since the formula with which it is calculated is partially based on the performance of the mutual-fund portion.

INSTITUTION OF THE

PUBLIC INQUIRY

A fundamental feature of the Swedish general-welfare society during its formative period was the use of thorough public inquiries, whose history dates back to pre-parliamentary days. Every reform and all proposed legislation was grounded in a lengthy public inquiry, often carried out in stages.

The first stage was often a study of practical matters, followed by a non-partisan parliamentary review, and sometimes concluding with a political commission whose task was to prepare the implementation of the proposed law or reform.

At each stage, great care was taken to solicit comments and suggestions from government agencies with the relevant expertise, political parties and all organizations with an interest in the proposal. The purpose was to ensure that all relevant issues were analysed and discussed from every possible angle prior to final decision. In this way, technical and practical matters were thoroughly illuminated in the political arena, and members of parliament could become well-informed about important matters on which they were to decide.

The ATP reform provides a good example of this procedure. The first public inquiry into pension reform was commissioned by the government in 1935. It was a one-man inquiry by the chief insurance inspector at the time, O.A. Åkesson, who submitted several proposals in the mid-1950s that were discussed very thoroughly. Then followed a political commission, led by government official Per Eckerberg, which presented its final recommendations in 1958.

The Eckerberg commission’s most significant contribution was to raise the pension ceiling, which had the effect of greatly expanding the range of eligible workers. This led to strong public support for the ATP system-- support that was much broader than suggested by the narrow margin of victory in the referendum that preceded adoption of ATP in 1960.

When Sweden’s economic policy was shifted in a neo-liberal direction during the 1980s,, the institution of careful public inquiries was bypassed. Examples of major decisions that were rushed through without the traditional process of review and consideration are the currency deregulation of the mid-1980s and the tax reform of 1990-91. The Social Democratic government’s revolutionary decision to apply for membership in the European Union was presented as a footnote to a budget proposal in 1989. The way in which the recent pension reform came about is described elsewhere in these pages.

All of these far-reaching changes were implemented out of public view by a narrow coterie of politicians.

In effect, what the new system does is to transfer a large portion of economic power from society as a whole to special interests, including banks, insurance companies, mutual funds and other financial institutions.

Further, and in contrast to the abandoned system, there has been a large transfer of capital out of Sweden as pension funds invest in foreign stocks. This hardly contributes to the stability and development of the Swedish economy, to which the entire pension system is supposed to be intimately linked.

For a large majority of citizens, the net result will almost certainly be a lower pension than would have been the case if the old system had simply been adjusted. In addition, there is a serious problem of social justice: Individuals who have worked equally long and hard will receive widely varying pensions, depending on the luck of the mutual-fund draw.

All of this has been justified by the quest for automatic financial stability. But the fact is that all financial systems require adjustments over time. The goal of automatic long-term stability is exceedingly elusive-- the pension-planning equivalent of a perpetual-motion machine. The unlikelihood of ever achieving that goal makes the subordination of the system’s social function all the more indefensible.

In short, the deficiencies of the new pension system are so profound that the question arises as to why it was ever adopted. The answer is probably to be found in the secretive, undemocratic process by which it was constructed and rushed into law.

Serving powerful interests

As with all fundamental issues in Sweden, the controlling power over pension reform was held by the Social Democratic Party (SDP) which has dominated national politics for more than sixty years. Since the assassination of Olof Palme in 1986, the SDP has undergone a transformation from a grassroots movement serving the interests of lower- and middle-income groups, to an increasingly autocratic apparatus dominated by a political elite (see ”The Price of Everything” and ”Great European Expectations”).

That transformation is now more or less complete, and the pension reform reflects the autocratic methods that the SDP leadership has established as praxis.

This can be seen clearly in the fate of the ”consultation process” that preceded the adoption of the new pension system. In accordance with SDP tradition, the party faithful were invited to study and debate alternative proposals for pension reform. An overwhelming majority of the 15,000 active members who participated in this process recommended that the old ATP system be retained, adjusted and further developed.

That was not the right answer. So the SDP leadership chose to misinterpret it and, instead, to conduct closed-door negotiations with representatives of four other political parties. The proposal that emerged from this secretive and hasty process-- without any significant input from available expertise-- was submitted for a review that was scandalously brief by Swedish standards: Members of parliament and other interested parties were granted a mere six weeks to study and comment upon an extremely complex technical document of some 1000 pages’ length.

Meanwhile, leading lights of the SDP embarked on a public relations campaign to soothe the mounting anxiety and outrage of the party faithful with an account of the proposed new system that was either remarkably misinformed or deliberately misleading.

Brave new democracy

In the ensuing bewilderment and confusion, the SDP and its centre-right collaborators were able to ram the reform through the parliament with a large majority. It is doubtful that more than a handful of the MPs who gave their consent had any real idea of what they were voting for.

That is what democracy looks like in the brave new world of Sweden, for a fundamental issue that will directly affect the lives of every citizen who reaches retirement age in the decades ahead.

It is a style of democracy and an approach to pension reform that corresponds quite well with similar trends in other countries. The Social Security system of the United States, in many ways similar to the abandoned Swedish system, has long been under attack by reactionary forces that have never forgiven Franklin D. Roosevelt for introducing such an element of ”socialism” into the American Way of Life.

Wild, undocumented claims of Social Security’s impending collapse have been a standard feature of U.S. politics for decades, and experiments in other countries are often cited as better alternatives. The market-oriented pension system of dictator Pinochet’s Chile was frequently served up as a suitable model-- until it sank in the wake of the market crisis that afflicted the Orient in the late 1990s.

A similar campaign was conducted against Sweden’s recently abandoned ATP system since its inception in 1960. The difference is that the Social Security system of the United States has, thus far, survived the propaganda assault by powerful special interests.

Now, it is the Swedish model of pension reform that is being touted as the best bet for the future. Some countries of Western Europe and the former Soviet bloc have been so effectively indoctrinated that they have modelled their own pension reforms on the new Swedish model. These include Latvia, Poland, Russia, Croatia and Mongolia-- societies that differ in many significant respects from each other and from Sweden.

But they do have one thing in common: The new Swedish pension system is very likely to have very unpleasant consequences for all of them, and especially for their most financially vulnerable citizens.

References

Robert L. Brown, Professor of Statistics and Actuarial Science at the University of Waterloo in Canada, has been president of both the Canadian Institute of Actuaries and the Society of Actuaries. In 1994, he won the third SCOR International Actuarial Prize for his essay, "Paygo Funding and Intergenerational Equity", which was published under the same title in the Transactions of the Society of Actuaries, Vol. 47, 1995. It is also available on the SOA web site.

The Economics of the Welfare State by Nicholas Barr was published by Stanford University Press in 1987.

Dr. Tapen Sinha is Professor of Risk Management & Insurance at Instituto Technologico Autonomo de Mexico, Mexico City, and also a professor at the School of Business, University of Nottingham, England. The essay cited here was presented at a Society of Actuaries conference, and can be found on the

SOA web site.

available in PDF format,

which is especially

suitable for print-outs.

Such documents can

only be accessed by

computers equipped

with the program,

Adobe Reader.

To access the PDF

version of this article,

click here.

already installed on your

computer, it is available

free of charge at the

Adobe website.

In his prize-winning essay, "Paygo Funding and Intergenerational Equity", Prof. Robert L. Brown makes a strong case for the pay-as-you-go principle in financing social security systems. He argues that a fully-funded social security scheme is no more financially secure than a paygo scheme. Both depend on the ability of the economy to create and transfer wealth. As far as social security is concerned, the funding mechanism is irrelevant.

In his essay, Brown quotes from The Economics of the Welfare State by Nicholas Barr: "The widely held (but false) view that funded schemes are inherently 'safer' than paygo is an example of the fallacy of composition.* For individuals, the economic function of a pension scheme is to transfer consumption over time. But, ruling out the case where current output is stored in holes in people's gardens, this is not possible for society as a whole; the consumption of pensioners as a group is produced by the next generation of workers. From an aggregate viewpoint, the economic function of pension schemes is to divide total production between workers and pensioners, i.e. to reduce the consumption of workers so that sufficient output remains for pensioners. Once this point is understood it becomes clear why paygo and funded schemes, which are both simply ways of dividing output between workers and pensioners, should not fare very differently in the face of demographic change."

Another interesting angle is provided by is the essay, "Can the Latin American Experience Teach Us Something about Privatised Pensions with Individual Accounts?", published in early 2002 by Dr. Tapen Sinha, who writes:

"In economic terms, there is no fundamental difference between a tax transfer pay-as-you-go social security scheme and a bond transfer, pay-as-you-go social security scheme. In a bond-transfer scheme, the bond issue posits an illusion of asset-creation. But, the sole purpose of the bonds is to engineer a transfer payment to the retirees. In a practical sense, benefits of the current retirees come from the contributions of current workers.

"To understand the equivalence, it is important to remember that a government bond is simply a promise by the government to make a payment in the future. A government promise to make a payment, to pay off a bond is not fundamentally different from a government promise to make a payment for social security benefits.

"If the government requires you to buy bonds and promises you future payments to retire the bonds, then it is not doing anything essentially different from requiring you to pay taxes and promising you a future transfer payment."

*The fallacy of composition is to assume that, if something is true for an individual, it must also be true for an aggregate of individuals. For instance: If I stand on my seat in the theatre I will get a better view; but if everybody does the same, nobody will have a better view.

— 10 June 2002

About the authors

Jan Hagberg, chief actuary at a large Swedish insurer, is Chairman of the Swedish Actuarial Society and a member of the International Actuarial Association.

Ellis Wohlner, Senior Vice President International of another major Swedish insurer, is a member of the Swedish Actuarial Society, the Society of Actuaries, the American Academy of Actuaries and the International Actuarial Association.